Scholar of political anthropology, the environment and island, Adriano Favole is an anthropologistProfessor at the University of Turin and author of books (the last is The Wild Way. Stories of humans and non -human per laterza). For years he has led research, particularly in the Oceania islandsreflecting on topics such as mobility, welcome and theinterdependence between humans and on the concept of identity.

Sunday 25 May, at 10 am, Adriano Favole will be a guest at Cultural anthropology festival dialogues on the man of Pistoiaon the stage of the Manzoni Theater, with the intervention Ancient and new nomadisposmsdedicated to travel as a condition originally of humanity and the analogies between traditionally migrants and new nomads of the global world.

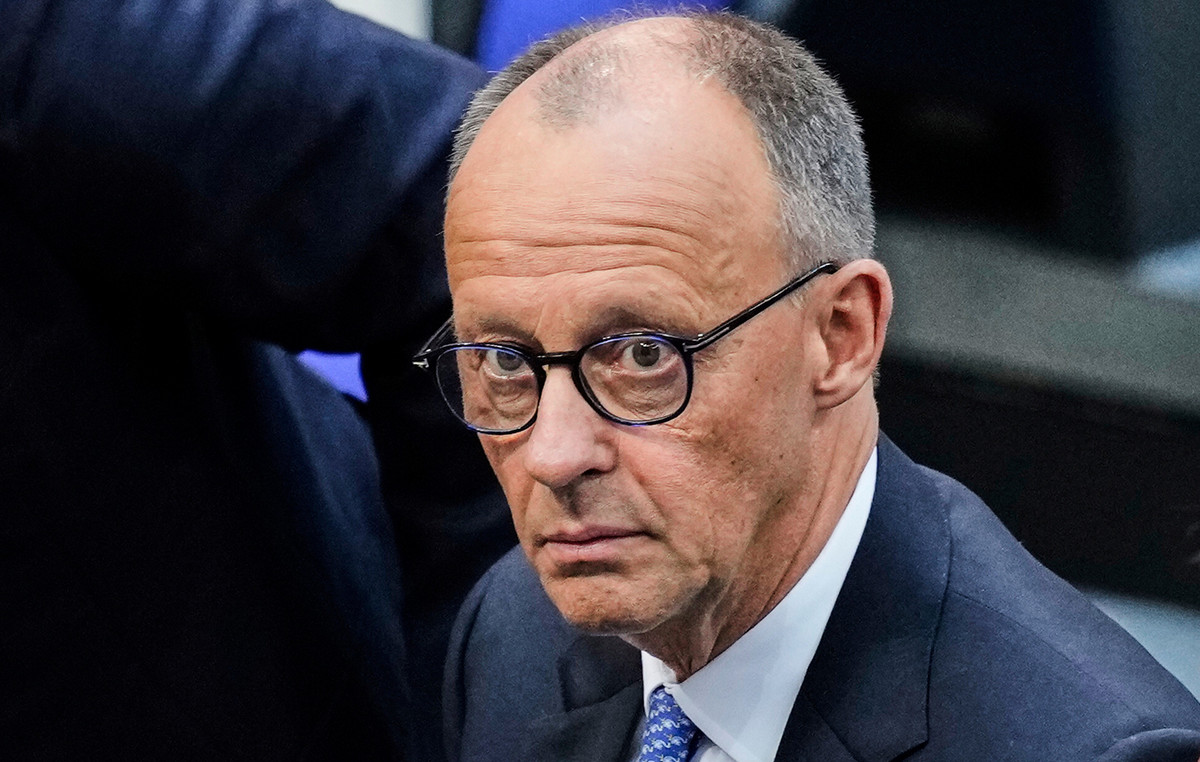

Adriano Favole. Photo: Laura Pietra

Professor, in what sense can we say that the human being has always been a nomadic species?

“The story of the expansion of our species on the planet tells us. For what we know today, the human being originated in Eastern Africa. And what is surprising is in a few tens of thousands of years – that, from a geological point of view, they are not so many – a species still demographically very small had expanded on most of the planet. In the most recent eras we find human beings that explore and adapt to living in the most diverse contexts. This is closely linked to the fact that we have evolved through culture: the ability to build tools, to extend and transform our body, up to making it capable of living in the poles as in deserts ».

Why can nomadic companies of the past still teach us something today? What is their topicality?

“The societies ofOceaniawhich are the ones I studied most closely, they had to adopt ecological and economic behaviors based on attention. They have always lived in environments with limited resources, little land and often little water. For this reason they have developed cultures attentive to balance and respect for resources. These companies speak to us today because they experienced, before us, of a finished world. It is not a question of automatically applying their models to our societies, but we can inspire us to those principles to rethink our lifestyles ».

She speaks of “leaving” and “welcoming” as two fundamental cultural traits. How do these practices reflect in contemporary nomadisposms?

“In pre-colonial oceanic society there was no idea that humanity was divided into distinct groups was much weaker. We are used to thinking about the world divided into states, and even before in peoples, ethnic groups, tribes. But if we look at the history of Oceania, we discover that it was not so. Oceania was a kind of chain of companies that gradually explored and occupied the Pacific islands – A process that lasted five thousand years. In this long time, interconnected companies have developed, based on a fundamental principle: the right to land “.

What is it about?

“Those who traveled in the Pacific knew they could land in certain areas: in the event of war, famine or raising of the sea level – which already occurred in the past – knew where to be able to take refuge. It was a world built on the beginning of leaving and being welcomed ».

Being able to leave and know that you are welcomed is a theme that speaks to us very much even today.

“In ancient Oceania there was no idea of foreign peoples, humanity was not as segmented as it is today. In Polynesian languages There is no word that corresponds to our “foreigner”. For example, in some areas where I work, the “foreigner” is said MATAA PULEwhich literally means “the gaze of a boss”: it is the same look of the navigator that comes from afar and looking for a place, which observes theisland. Whites are also called like this ».

The foreigner is nothing else from you, with this perspective.

“That’s right, it is not a radical otherness: the other is first of all a human being. Then you can decide whether to welcome it or not, but there is no raid, nor ethnicization. There is a nice chapter in the book The dawn of everything by Graeber and Wengrow, published by Rizzoli, who is titled Hospitality chains. It is very illuminating: it shows how evident evidence was not made that distinct peoples existed in prehistory. Rather, exchange networks emerge, relationships – even conflicting, of course – but not watertight compartments. Perhaps, as the authors suggest, the states were the ones who invented peoples, and not vice versa ».

Today the movements are much easier and in our traveling company is a fundamental right. But if you leave is not a problem, how do we get it instead with the welcome?

«On leaving you say that we are quite equipped? More or less: we, with an Italian and European passport, can go to over 120 countries – sometimes with visa, sometimes without. But there are passports, for example in some African countries, which allow access to very few states, if not anyone. So no, we are not all free to leave. And perhaps this is an even bigger problem than welcoming. Graeber says: “Not being able to leave cancels all my other freedoms”. We would need a world where passport was a universal document ».

Continuing to reflect on welcoming, what difference is there, if there is, between travel and migration?

«It is no coincidence that we distinguish between the two words, someone puts them together and speaks of mobility, but more often they are seen as antipodes and is indicative because it is the demonstration that we divide between a welcome that is always open for those who come from rich countries and the migrations that instead see as slices of poverty. That then this is not true, because in reality today migrations are mostly explained with the desire to improve their conditions. Just look at the Italian data: to migrate now they are mainly graduate people who are not satisfied with living conditions in Italy ».

Does mobility within the states that impact has on the construction of collective identity?

«I think it is always useful to overturn the question a little. Many are worried about what happens to us because migratory waves arrive. But the Italians who migrate elsewhere how other cultures change? Do we ever think that these Italians are contaminating elsewhere? ».

This reflection can also be done to tourists and digital nomads. Communities increasingly manifest malaise for their presence.

«What causes problems is when the numbers of the tourism of digital nomads become so high as to impact from an ecological point of view, as well as cultural on a place. Today we speak as much of Overurism as if it were a great novelty, but I who live in Piedmont and that I know Liguria well I see that that region is 40 years that has over -sided problems: cement, price raising, young people’s escape, pollution, lack of schools etc. I am not convinced that the problems arise from intercultural coexistence, the major problems are of an ecological, demographic, economic order or linked to prejudices between the people who imagine that the other is dangerous “.

I know she doesn’t like the word identity. How come?

«Identity is a slightly poisonous word because it comes from idemwhat is the same as itself. And therefore behind this word there is the idea that societies in itself are identical to themselves over time, except for someone to threaten their identity. But when are the companies ever identical to themselves over time? When we ever as individuals, are we identical to ourselves in our life? We have lines of continuity, of course, otherwise we would be completely ungovernable and individed, but in our country there is a frightening rhetoric on identity, which becomes a way to exclude and trace insurmountable boundaries “.

A revolutionary thought for today, where do nationalisms and obsessions of defense of borders abound?

“I am criticized and you say:” You want a cosmopolitan world you who are one day here, one day you are there “. No, I think it is important, anywhere you are, living on relationships: the family, the kinship, the neighborhood, the friends, the work. Not identity, but interdependence: this is a word that I like ».

Do you believe that traveling can help you think this way?

«Yes with the experience of experience, the relationship journey, the journey of discovery. We are not all explorers and it does not matter to go to the other side of the world: where we will go to millions of people, but we must want to hear people, to relate to them, not to go and see the slides of a landscape from the windows of a car. The experience of experience shows you the limits of the concept of identity, because you immediately realize that there are other styles of life, but also of the profound similarity between human beings ».

Is there a meeting or place that has changed its way of seeing the world a little more than the others?

«For an anthropologist it is generally the place where the first long field research is done. Here, so for me it was certainly this small Polynesian island called Futuna (in the southern part of the Pacific Ocean), in which I was for the first time between ’96 and ’97. There the inhabitants live in huts open on all four sides: the houses are places where you enter freely, the entrance is announced, but it is an almost public space. The places of intimacy, the gardens, the vegetable gardens. And now I can’t stand the houses with curtains anymore, for example, they make me feel oppressed. A short or long journey must have this virtue: to force you again to be plastic, a bit like a child, you have to re -tear, get up and trust. Trust is the key: believe that there is someone who will take care of you. Not everyone saw the other as a dangerous, wary, foreign person. “

Source: Vanity Fair

I’m Susan Karen, a professional writer and editor at World Stock Market. I specialize in Entertainment news, writing stories that keep readers informed on all the latest developments in the industry. With over five years of experience in creating engaging content and copywriting for various media outlets, I have grown to become an invaluable asset to any team.

.jpg)