This article is published in issue 17 of Vanity Fair on newsstands until April 23, 2024.

If you ask ChatGpt-4 to imagine the plot of a dystopian film about an imminent civil war in America, you will get the following answer: «In the very near future, the United States is on the brink of collapse. Political polarization, economic crises and environmental disasters have deeply divided the nation. In this context of growing tension, an unexpected spark starts a devastating civil war.”

OpenAi's artificial intelligence is trained with information that reaches up to 2021, so we can consider its answers not a comment on current events, but a kind of squeezing of the collective unconscious. At the first interactions ChatGpt never offers creativity, but the most probable response, the most shared one.

This test is enough to understand that the most discussed film these days – Civil War by Alex Garland, released on April 18th in Italy – does not claim to suggest extreme scenarios or imagine alternative futures. On the contrary, it presents itself as a long trailer for the news of the coming years, or perhaps months. The United States is divided, there is a new civil war, an authoritarian and besieged president is barricaded in the White House, the country is tormented by riots in the cities, shootings, explosions, armed gangs controlling the streets, there are “forces Westerners” marching on Washington. The film follows a group of journalists who try to get to the capital to report the decisive developments, they succeed but – spoiler – Civil War does not provide any happy ending.

If we treat this film as ChatGpt's answer, that is, as a compact summary of what we already know about America and the growing polarization of our society, it is much richer in stimuli than as an entertainment product. The plot is practically not there, the narrative gaps are more noticeable than the full ones. From The Walking Dead to The Last of Uswe know that in every post-apocalyptic scenario what matters is the reaction to the catastrophe, not its origin which is never detailed.

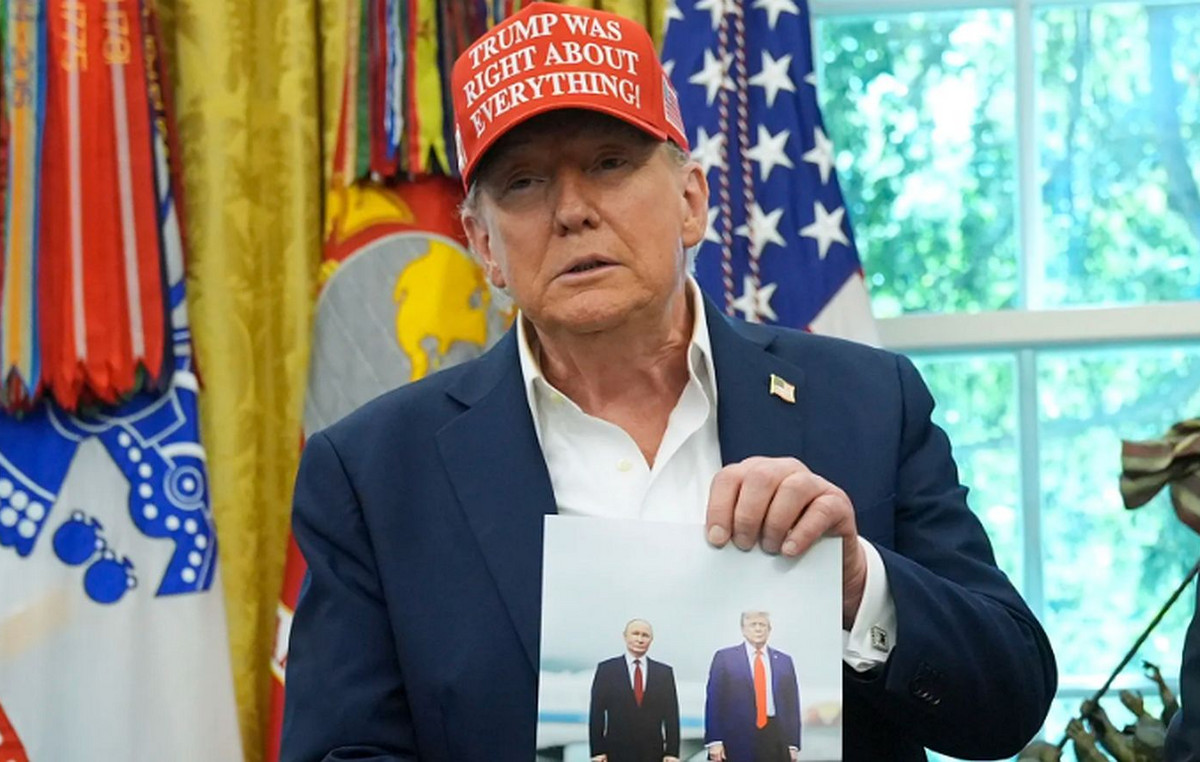

In Civil War an “Antifa massacre” is evoked as the trigger for the violence, that is, some massacre of radical demonstrators (ordered by Donald Trump? Who knows), and this already says something about the idea of civil war that Americans have today. Not a re-edition of the one from 1865, but a blaze of hatred and violence as quick as one shitstorm social media that degenerates towards massacre.

In the original Civil War, the conflict was over the social and economic structure of the United States and also its soul: the Southern states, which thrived on cheap slave labor, had opposing interests to those of the North, which pushed for a more industrial, productive economy and open to international trade. In the conflict imagined in Garland's film, we fight without a reason and without an objective: the most dangerous militiamen that Lee Smith, the war photojournalist played by Kirsten Dunst, and the other journalists encounter are those without a flag. They shoot because someone else shoots, they kill because the spirit of the times requires it.

After September 11, 2001, every American blockbuster for years included the destruction of New York and some processing in computer graphics of the trauma of the Twin Towers. As if only reviewing the news through the filter of caricatural fiction could allow us to digest it. And so Civil War transfigures the not yet absorbed traumas of recent American history: the riots of Black Lives Matterafter Minneapolis police killed George Floyd in 2020, the assault on Capitol Hill of 6 January 2021, massacres in schools.

With the speed of a swipe through Instagram reels, director Alex Garland also scrolls through fragments of Vietnam, mass graves from the Shoah. Always transfigured in the key of the civil war, the only type of conflict experienced at home by the Americans, protected from land or air battles by two oceans.

Civil Warhowever, does not summarize America's fears, but only one part, what Donald Trump fears and considers its base morally compromised and doomed to violence. The exceptions to this collective narrative are as rare as they are powerful, you see American elegy by JD Vance, story of a poor white family in Ohio. The novel gave the author a Netflix adaptation, a Senate seat and presidential ambitions.

In Civil War there are no nuances, complexity is banished: at the center there is only violence. And this involves narrative sacrifices that are more interesting than what is shown. Director Alex Garland centers the story on a group of journalists, more anachronistic than heroic: the veteran photojournalist, a Reuters reporter looking for adrenaline rushes rather than scoops (Wagner Moura), an aspiring correspondent (Cailee Spaeny), a editor of New York Times (Stephen McKinley Henderson) which should embody the glories of a past journalism.

The film presents journalists as upright reporters who report the facts without being influenced by their own opinions. But the press and television were the prime mover of American polarization. With Fox News by Rupert Murdoch, of course, but also with the New York Times who hides inconvenient news about Joe Biden and campaigns for subscriptions thanks to an obsession with Trump.

Furthermore, journalists at the front of Civil War they have no audience, they mingle with soldiers on the battlefield to observe brawls and massacres, but where are their readers or spectators? Only in one scene does Kirsten Dunst try to upload some photos to a server, no one knows for whom: the media that polarized America also destroyed their audience transformed into fans.

The protagonists of the film despise the Americans – like the parents of Kirsten Dunst's character and that of Cailee Spaeny – who live far from the front and are not interested in the war. But it is not very clear why the voyeurism of reporters who want to stay in the midst of violence without fighting should be evidence of superior civility.

The entire narrative structure requires the disappearance of technology: Kirsten Dunst's vocation to professional martyrdom would be completely useless in a world of smartphones and social media, because every explosion, every hanging, every lynching would be filmed and posted from every possible angle. So Alex Garland cancels the Internet and everything elseso as to make a return to certain digital cameras plausible from the beginning of the millennium.

In January 2021, social media (and in particular Twitter) were decisive in igniting the spark of civil war that was the Trumpian assault on Parliament. Garland imagines that the violence would end up shutting down the Internet and freeing us from constant connection, in an almost liberating return to a wild pre-Internet world. This, perhaps, is the film's boldest vision: that digital platforms can be shut down only because fights fueled by algorithms have become real violence.

In 2021, faced with the assault on Capitol Hill, from Twitter to Facebook, from PayPal to SnapChat, the platforms closed Donald Trump's accounts and thus established who is really in charge. In the age of digital intelligence we can only hope that the self-preservation instinct of algorithms can stop the violence it has fueled, before it is too late.

To subscribe to Vanity Fair, click here.

Source: Vanity Fair

I’m Susan Karen, a professional writer and editor at World Stock Market. I specialize in Entertainment news, writing stories that keep readers informed on all the latest developments in the industry. With over five years of experience in creating engaging content and copywriting for various media outlets, I have grown to become an invaluable asset to any team.