By Javier Blas

During US President Biden’s trip to Saudi Arabia, the world was so focused on how Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman would respond to calls for more oil that they missed an important fact: the level at which oil production will peak. in Saudi Arabia.

It is much lower than many expected. It is lower than the Saudis have ever indicated. And as the world continues to thirst for fossil fuels, it creates long-term problems for the global economy.

For years, Saudi oil ministers and royals have sidestepped one of the most important questions facing the energy market: what is the long-term cap on the Kingdom’s oil reserves? The guess was that they could always pump more, and for longer. If the Saudis knew the answer, they kept it secret. And then, almost casually on Saturday, Prince Mohammed revealed the news, that the final maximum capacity is 13 million barrels per day.

Prince Mohammed framed his response by stressing that the world – and not just countries like Saudi Arabia – must invest in fossil fuel production over the next two decades to meet growing global demand and avoid energy shortages. “The Kingdom will do its part as it has announced an increase in its production capacity to 13 million barrels per day, after which the Kingdom will not have any additional capacity to increase production,” he stressed in a speech.

Recap: Saudi Arabia, the owner of the world’s largest oil reserves, is telling the world that in the not-too-distant future “it will have no additional capacity to increase production.”

The first part of this announcement was familiar. In 2920 Riyadh ordered state oil giant Saudi Aramco to begin a multi-year, multibillion-dollar program to boost peak production capacity to 13 million barrels by 2027, up from 12 million. The project is underway, with the first small additions coming online in 2024, followed by larger ones over the next three years.

But the second part was entirely new, setting a hard ceiling far below what the Saudis had discussed in the past. In 2004 and 2005, during Riyadh’s major expansion, the Kingdom made plans to expand its pumping capacity to 15 million, if needed. And there was no indication that even this increased level was a ceiling.

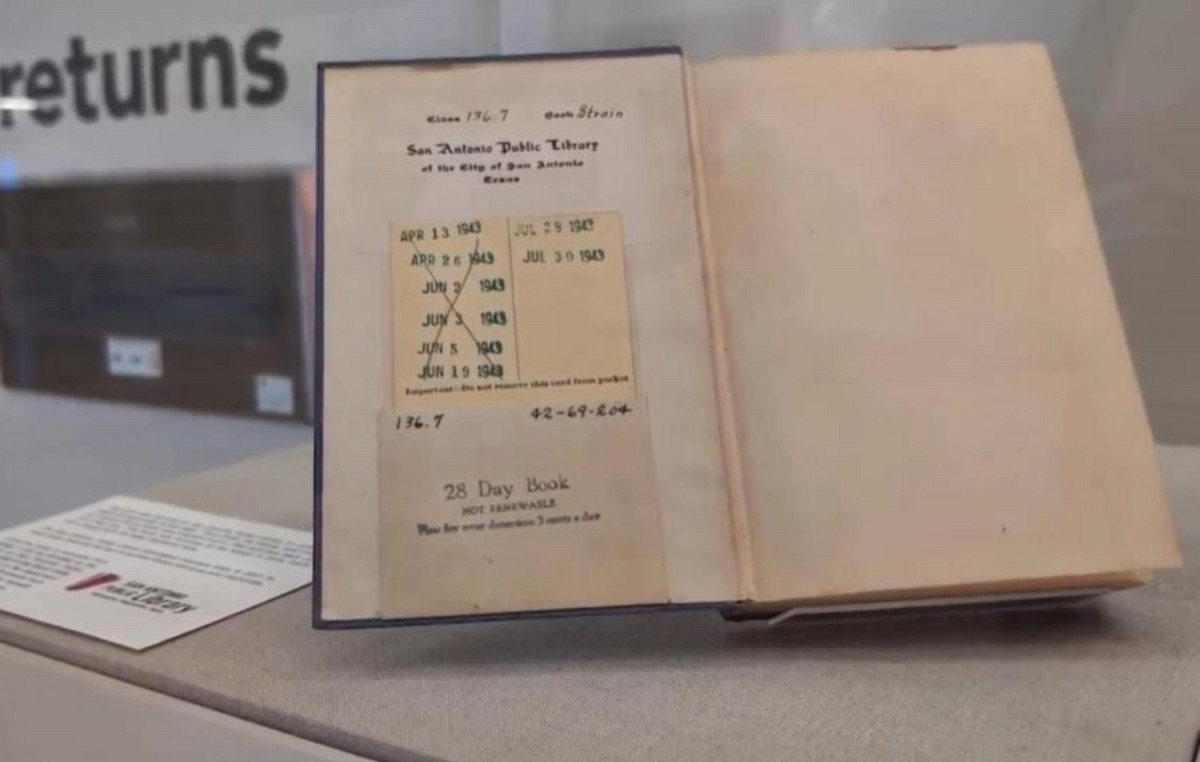

For example, Aramco executives told the CSIS think tank in Washington in 2004 that the company could maintain production levels of 10, 12 and 15 million barrels per day for 50 years if needed. At the time, Riyadh was fighting the views of the late Matt Simmons, author of the much-discussed book “Twilight in the Desert: The coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy.” The book argued that peak Saudi oil production was too close.

One reason Saudi Arabia is now setting a lower production cap may be related to climate change. Uncertain about future demand growth, Riyadh may appreciate that it is foolish to spend billions of dollars on new capacity it may not need.

In his speech, Prince Mohammed stressed “the importance of assuring investors that the policies do not pose a threat to their investments”, with the aim of avoiding “their reluctance to invest”. I don’t think the prince was talking about Wall Street money and hedge funds when he said “investors.” It’s a term that also covers Saudi interests.

Forecasting oil demand is as much an art as it is a science—and the kingdom is conservative by nature. A decade ago, Saudi Arabia’s then energy minister, Ali Al-Naimi, pointed out that Saudi Arabia would be “lucky” to pump more than 9 million by the early 2020s. “Realistically, based on all the projections I’ve seen, including ours, there’s no reason to go past 11 million by 2030 and 2040.” The reality has become much more positive than he himself expected. Next month, Aramco will increase daily production to just over 11 million barrels.

If demand proves stronger in the coming years than the Saudis now expect, the Kingdom may simply revise its investment plans and announce that it is in a position to boost production further. But Prince Mohammed sounded rather confident in enacting that 13 million cap. If it’s not money that’s limiting, then it must be geology.

For years, Saudi Arabia has been bringing new oil fields online to compensate for the natural decline of its aging reservoirs, and has allowed Ghawar, the world’s largest oil field, to operate at a slower rate. As it seeks to boost production capacity rather than simply compensate for natural decline, Aramco is increasingly turning to more expensive offshore reservoirs. Perhaps Riyadh is less confident about its ability to add new oil fields. Ghawar itself is drawing much less than the market expected. For years, logic said the field was capable of producing 5 million barrels, but in 2019 Aramco revealed that Ghawar’s maximum capacity was 3.8 million barrels.

If the obstacle to boosting production is geology, rather than pessimism about future oil demand, the world faces a tough time if consumption becomes stronger than currently expected. For now, peak Saudi production is a relatively distant topic, at least five years away. More pressing is whether Riyadh will be able to maintain its current output of 11 million – something it has achieved only twice in history, and then only briefly – let alone increase it further. But this limit will matter towards the end of the decade, and perhaps even sooner.

Despite widespread talk of peak oil demand, the truth is that, for now at least, consumption continues to rise. The world is heavily dependent on three nations for crude oil: the US, Saudi Arabia and Russia. Together, they account for 45% of the world’s oil supply. With US investors reluctant to finance a return to the days of “drill baby, drill”, US output growth is now slower than it was in the 2010s. Russia faces an even more ominous outlook as the influence of Western sanctions not only hit the current supply, but also hinder its ability to expand in the future.

In an era of climate change, Saudi production will be ironically even more important. And the riyadh has now publicly set a strict limit on how much it can draw. This time, oil demand should peak – because there will be no additional supply. Ultimately, there are only two paths to this outcome. Voluntarily, by switching to low-emission energy sources such as nuclear or wind power. Or with much higher oil prices, faster inflation and slower economic growth. If we do not follow the first path, we will be forced to follow the second.

Source: Bloomberg

I’m Ava Paul, an experienced news website author with a special focus on the entertainment section. Over the past five years, I have worked in various positions of media and communication at World Stock Market. My experience has given me extensive knowledge in writing, editing, researching and reporting on stories related to the entertainment industry.